When organizations talk about artificial intelligence tools training, they often speak as if the phrase has a shared meaning. It does not. For some, it refers to learning how to write prompts in a chatbot. For others, it means retraining entire departments around automated decision systems. In public policy, it can mean national curriculum reform. In corporate strategy, it can quietly mean workforce triage.

The lack of a shared definition is not accidental. It reflects how unevenly AI capabilities are being absorbed into real work.

AI tools training is less a single discipline and more a collision zone between literacy, labor economics, regulation, and technical practice. Treating it as a narrow upskilling initiative misses why it has become unavoidable.

The quiet shift from optional skill to baseline expectation

Five years ago, AI training was framed as an advantage. Today, it is increasingly treated as infrastructure.

Market data around AI in education and training points to sustained, high growth not because AI tools are novel, but because organizations cannot function smoothly without them. The pressure is not only technological. It is organizational.

Research from institutions like Harvard Business Review and Boston Consulting Group describes reskilling for AI as a strategic requirement rather than an innovation experiment. This language matters. Strategy implies risk management. It implies long time horizons. It implies that opting out is no longer neutral.

Without structured training, AI adoption tends to concentrate in small pockets. A few employees become highly productive. Most remain peripheral. That imbalance creates internal inequality, governance gaps, and eventually resentment.

What gets labeled as training is often only exposure

A common failure pattern is mistaking exposure to AI tools for training.

Many programs focus on showing what AI can do rather than building the capacity to judge when and how it should be used. This is why “AI literacy” has emerged as a separate category. Literacy is not fluency. It is the minimum required to avoid misuse.

Frameworks promoted by organizations such as UNESCO and the European institutions behind the European AI Act stress this distinction. Literacy means understanding limitations, bias, and failure modes. It means recognizing when outputs are plausible but wrong.

Training that skips this layer tends to produce overconfidence rather than competence.

The economic logic behind large scale AI reskilling

Case studies of enterprise AI training reveal a pattern that contradicts popular narratives.

In several documented programs, large organizations reported measurable outcomes such as reduced service resolution times, lower operational costs, and improved employee retention. These gains did not come from replacing workers. They came from changing how work was structured around AI systems.

The implication is uncomfortable for simplistic automation stories. AI tools training functions less as a cost cutting lever and more as a coordination mechanism. It aligns human judgment with machine output. Without training, the same tools often increase friction rather than efficiency.

This is why reskilling initiatives increasingly sit with executive leadership rather than HR alone.

Regulation is quietly forcing the issue

Policy pressure is one of the least discussed drivers of AI training.

The European Union has embedded AI literacy into its regulatory approach, especially for high risk systems. The expectation is not that every worker becomes an engineer, but that decision makers understand the systems they oversee.

Similar logic appears in national strategies such as India’s IndiaAI Mission and large scale teacher training initiatives in South Korea. These programs treat AI skills as public capacity, similar to digital literacy or basic statistics.

Once regulation assumes a baseline of understanding, training stops being optional. It becomes compliance adjacent.

Why most AI training programs feel unsatisfying

Across sectors, the same complaints surface repeatedly.

Training is often tool specific, which makes it brittle. Interfaces change. Models are replaced. Skills tied too closely to a single product decay quickly.

Another issue is abstraction. Ethics modules are frequently theoretical, detached from real scenarios. Technical modules sometimes ignore deployment, monitoring, and governance. Non technical programs may avoid data literacy entirely, leaving participants unable to question outputs.

The result is a strange asymmetry. People are encouraged to use AI tools more, but not equipped to challenge them.

The missing layer is judgment, not knowledge

Effective AI tools training does not revolve around mastering features. It revolves around developing judgment under uncertainty.

That includes knowing when not to use AI, how to validate outputs, how to recognize biased data, and how to escalate concerns. It also includes understanding how incentives shape AI behavior inside organizations.

This is why newer curricula increasingly integrate governance, risk, and accountability alongside technical content. It is also why older machine learning bootcamps feel incomplete by today’s standards.

Governments face a different scaling problem

Public sector AI training operates under different constraints.

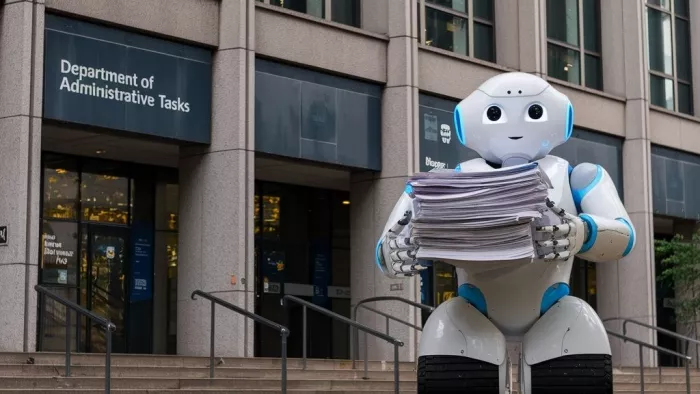

Agencies such as the U.S. General Services Administration run role based AI training tied to executive orders and procurement rules. The challenge is not enthusiasm, but heterogeneity. One program must serve policymakers, analysts, IT staff, and frontline workers.

National strategies often emphasize training teachers and trainers first. Without this multiplier effect, AI education cannot scale. This bottleneck is now widely acknowledged, though not easily solved.

Where AI tools training is heading

Several trends are becoming visible.

AI is increasingly used to deliver AI training itself, through adaptive learning systems and automated feedback. This raises obvious concerns around privacy and overreliance.

Skills frameworks are becoming dynamic rather than static, with AI used to infer emerging roles and competencies from labor market data. Organizations like the World Economic Forum have begun formalizing this approach.

Sector specific standards are also emerging. Finance, healthcare, and public administration are developing differentiated expectations for AI competence based on risk exposure.

Over time, AI fluency may resemble data protection training today. Mandatory, audited, and role dependent.

A more realistic way to think about AI tools training

Artificial intelligence tools training is not a course, a certificate, or a workshop. It is an ongoing negotiation between technology, work, and responsibility.

Programs that treat it as a one time intervention tend to fail quietly. Programs that embed it into workflows, governance, and career progression tend to persist.

The real question is not whether people can use AI tools. It is whether they can use them without surrendering judgment. Training that does not address that question is unlikely to matter, regardless of how modern the tools appear.

In that sense, AI tools training is less about preparing for the future and more about keeping human agency intact in the present.

Comments